- Table of Content

- 1.Almost spotles...

- 2.Solar Cycle 25...

- 3.Restoring cont...

- 4.Review of Sola...

- 5.International ...

- 6.PROBA2 Observa...

- 7.Noticeable Sol...

- 8.Geomagnetic Ob...

- 9.Review of Iono...

- 10.The SIDC Space...

- 11.Upcoming Activ...

2. Solar Cycle 25 reached its maximum in October 2024

3. Restoring contact with Proba-3

4. Review of Solar and Geomagnetic Activity

5. International Sunspot Number by SILSO

6. PROBA2 Observations

7. Noticeable Solar Events

8. Geomagnetic Observations in Belgium

9. Review of Ionospheric Activity

10. The SIDC Space Weather Briefing

11. Upcoming Activities

Almost spotless

Over the last few weeks, the Sun showed solar observers two different faces. Early February, various sunspot groups were visible including the large active region NOAA 4366 (SIDC Sunspot Group 784 - https://www.sidc.be/services/event-chains/sunspots ). Two weeks later, the Sun was nearly devoid of any sunspots, in particular on 22, 23 and 24 February. This can be seen in the SDO/HMI images underneath, taken on 6 and 22 February.

SILSO, short for "Sunspot Index and Long-term Solar Observations" (https://www.sidc.be/SILSO/home ), is the World Data Center for the production, preservation and dissemination of the international sunspot number. The sunspot number is calculated as 10 times the number of sunspot groups to which then the total of individual sunspots is added. SILSO bases these numbers on a worldwide network of more than 80 observers. Every year, this parameter is used in hundreds of research papers on solar physics, climate change, and several space weather and space climate related topics.

In its most recent monthly compilation of the provisional international sunspot numbers (https://www.sidc.be/products/ri_hemispheric/ ), SILSO reports for 22, 23 and 24 February daily sunspot numbers of respectively 4, 8, and 6 - as highlighted on the annotated report above. At first, these values may sound impossible, as the lowest sunspot number that an individual observer can have is -aside 0 of course- 11 (1 sunspot group with 1 sunspot). However, one should not forget that there's also a correction factor for each observer accounting for various influences such as the diameter of the telescope. Specola Solare Ticinese in Locarno serves as the reference station. Also, the daily sunspot number is the average of the observers that submitted reports for that day. It's no surprise then that during days with only few and very small sunspots popping in and out of existence, the sunspot number for that day ends up somewhere between 0 and 11. This can indeed be seen in white light images underneath where some tiny sunspots appear just for a few hours before already disappearing again. Small sunspots were indeed visible for a few hours during each of the 3 days, but is was a close call.

A spotless day is a day with no sunspots, equivalent to a daily sunspot number of 0. The last spotless day dates already back to 11 December 2021 (SILSO). It marked the 848th and last day with a spotless solar disk during the transition from the previous solar cycle 24 to the current solar cycle 25. Though there are a few exceptions, the number of spotless days may give a first rough idea on the strength of the upcoming solar cycle: a weakly to moderately active cycle (many spotless days), or a moderate to strong solar cycle (only few spotless days). It also gives an idea on the evolution of the cosmic ray intensity, i.e. the higher the number of spotless days, the higher the flux of cosmic rays as measured by neutron monitors on the Earth's surface (SC25 Tracking page at https://www.stce.be/content/sc25-tracking#cosmicrays ). SILSO has a Spotless Days page (https://www.sidc.be/SILSO/spotless ) to follow this transition. It will be activated for the next solar cycle transition around the 10th spotless day, most likely in 2027. The chart below shows the 25 years with the highest number of spotless days since 1849.

Solar Cycle 25 reached its maximum in October 2024

In 2019, the Solar Cycle Prediction Panel (www.swpc.noaa.gov/news/solar-cycle-25-forecast-update) convened to gather and combine predictions for the still infant Solar Cycle 25. The results of this gathering were published shortly thereafter: the�Solar Cycle Prediction Panel expected the cycle maximum value of the smoothed monthly sunspot number to be in a very narrow range between 105-125 with the peak occurring between November 2024 and March 2026. �

Seven years later, we can now say we have reached and passed the maximum and the predictions from 2019 appear to have been significantly lower than reality. Of course, in terms of prediction accuracy, the closer we are to the actual maximum, the more the various prediction methods will converge. Indeed, in 2024, SILSO predicted a maximum SN between 138 and 161 that would take place sometime between May and October 2024, while�NOAA predicted a similar range between 137 and 164 but within a broader time window between February 2024 and January 2025 (See https://testbed.spaceweather.gov/products/solar-cycle-progression). The results have been�confirmed by SILSO in 2025 (www.sidc.be/SILSO/DATA/SN_ms_tot_V2.0.txt): the maximum value of the monthly smoothed sunspot number for Solar Cycle 25 was reached in October 2024 and is 161 (see figure 1), versus 159 for September and 157 for November 2024.�

Figure 1- Solar Cycle 25 and its maximum seen in October 2024, as well as the 12-months ahead predictions that show a decreasing trend for September 2025 and February 2026, thus confirming the trend.

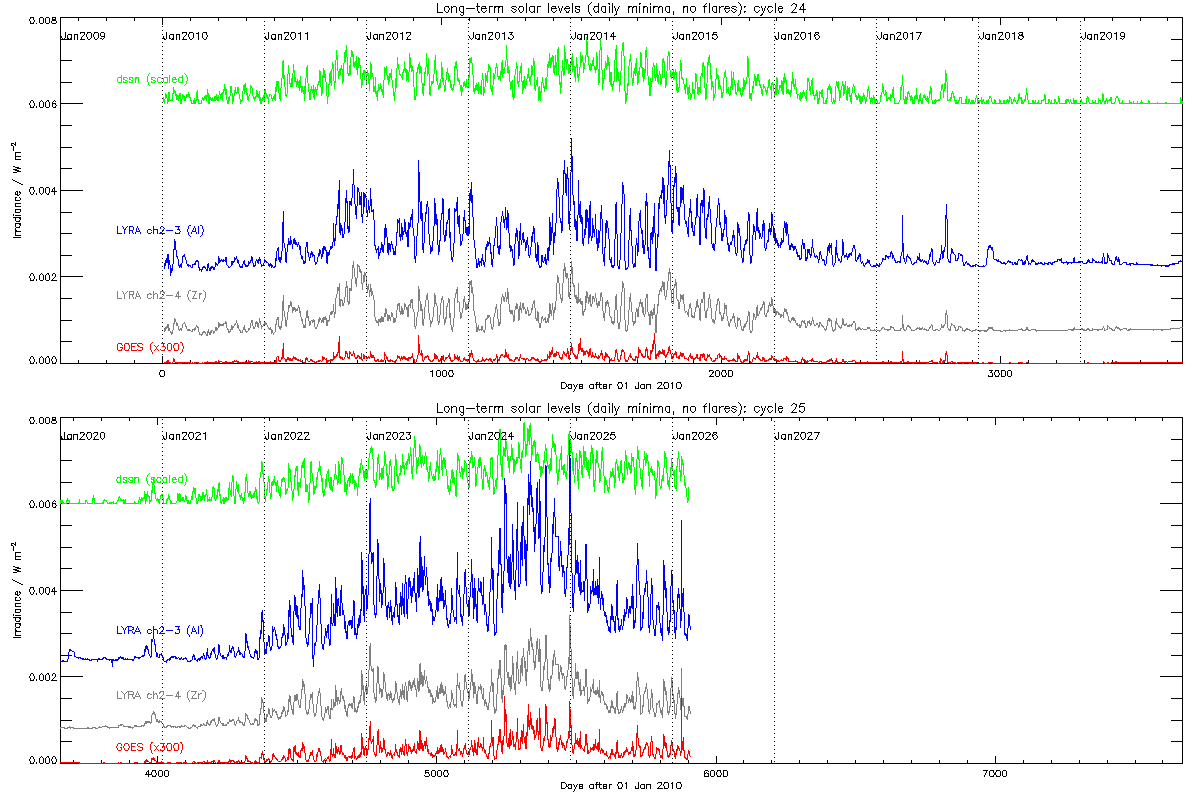

The results are confirmed by a simple calculation on the Lyra (Ref1, Ref2) and GOES (Ref) data, by using a similar method. Instead of a 13 months-smoothed value, we use a +/- 198 days window on the daily data (which corresponds to 6,5 months on each side) and find:�

* LYRA ch2-3 (Al) peaks with 0.0047 W/m2 on 01 Oct 2024

* LYRA ch2-4 (Zr) peaks with 0.0020 W/m2 on 29 Sep 2024

* GOES peaks with 1.815e-6 W/m2 also on 01 Oct 2024

* The daily sunspot number (smoothed in the same way) peaks with 159 on 20 Oct 2024, just 19-21 days later than LYRA and GOES.

These numbers can be seen in Figure 2 below and are�all consistent with a 13 months-smoothed peak in October 2024 for solar cycle 25.�

Figure 2 - +/- 198 days smoothed daily total Sunspot Numbers (https://sidc.be/SILSO/datafiles), LYRA channels 2-3 and 2-4 and GOES flux all scaled over solar cycle 25.

What this entails for the SIDC team, is that, at this stage of the Solar Cycle, the Sun is very active, and will remain at a similar level of activity well into 2026. Since the beginning of 2024, many large and complex active regions have crossed the solar disk regularly driving the daily sunspot number to well above 250 as can be attested by the�SIDC/USET image for 7 August 2024 (figure 3).�

Figure 3- White light image of the photosphere of the Sun taken on August 7 2024.

These active regions have often been the source of strong solar flares, and the associated solar eruptions, when they are not confined and are earth-directed, strongly affect the Earth�s magnetic field. The important aurorae thus created are sometimes visible from countries further away from the polar regions, such as in May 2024 when the colourful display was also visible from Belgium (see stce.be/news/701/welcome.html). While storms of this magnitude occur approximately once every 12.5 years, the length of this specific storm was unusual, expected only once every 41 years (doi.org/10.1029/2024SW004113). There were also important storms in October 2024, June 2025 (stce.be/news/771/welcome.html) and more recently in January 2026 (stce.be/news/802/welcome.html). These major solar storms and their impact on Earth help improve the accuracy of Space Weather forecasting as they enable us to sample solar events with the full range of instruments at our disposal today.

2026 still holds a lot of sunspots to count and a interesting activity for our Space Weather team!

Restoring contact with Proba-3

An anomaly onboard the Proba-3 mission’s Coronagraph spacecraft led to loss of contact between the spacecraft and ground control. The root cause of the anomaly is under investigation and mission teams are working hard to recover the situation.

Read the full message from ESA here: https://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/Space_Engineering_Technology/Work_ongoing_to_restore_contact_with_Proba-3_s_Coronagraph

Review of Solar and Geomagnetic Activity

WEEK 1313 from 2026 Feb 23

Solar Active Regions and flares

Solar flaring activity was generally low throughout the week, with predominantly C-class flares and one M-class flare. The strongest flare was an M2.3 flare from the east limb (SIDC Flare 7072), peaking at 15:59 UTC on February 25.

The number of active regions (ARs) on the visible disk increased during the week, from one at the beginning of the week to seven by March 01. Early in the week, SIDC Sunspot Group 799 (magnetic type beta) emerged and then decayed into a plage by February 24. SIDC Sunspot Group 800 (magnetic type alpha), rotated onto the disk on February 25. By mid-to-late week, the most complex region was SIDC Sunspot Group 803 (NOAA Active Region 4380), which after rotating onto the visible disk from the east limb, was classified as beta-gamma and subsequently showed a gradual decrease in magnetic complexity. Additional regions rotated onto the disk or emerged during the week, contributing to the increase in the number of active regions on the visible disk by the end of the period.

Coronal mass ejections

A coronal mass ejection (SIDC CME 629) was observed in LASCO/C2 coronagraph data starting at around 07:00 UTC on February 25. The CME was directed primarily to the north from Earth's perspective and was most likely associated with a filament eruption observed around 06:00 UTC on February 25 near the central meridian in the mid-latitude northern hemisphere. The bulk of the ejecta was expected to miss Earth, but a glancing blow could not be excluded around February 28. No clear arrival signatures attributable to this CME were identified in near-Earth solar wind observations during the period covered by this report.

Coronal Holes

A recurrent, negative polarity, equatorial coronal hole (SIDC Coronal Hole 147) was the dominant feature early in the week, driving a high-speed stream that influenced near-Earth space.

In addition, a small, mid-latitude, positive polarity coronal hole (returning SIDC Coronal Hole 151) was reported crossing the central meridian during the week.

Proton flux levels

The greater than 10 MeV proton flux remained below the 10 pfu threshold throughout the week.

Electron fluxes at GEO

The greater than 2 MeV electron flux measured by GOES 18 and GOES 19 was generally around or above the 1000 pfu threshold during most of the week, with brief intervals below the threshold.

The 24-hour electron fluence was at normal levels early in the week and was predominantly at moderate levels from midweek through the end of the week.

Solar wind

Solar wind conditions transitioned from enhanced conditions early in the week to mostly slow solar wind conditions by the end of the week.

The week began under the continuing influence of a high-speed stream associated with SIDC Coronal Hole 147, with elevated solar wind speeds typically between 560 and 740 km/s early in the period. Interplanetary magnetic field values were generally up to around 10 nT, with the Bz component fluctuating between about -9 nT and 9 nT at the beginning of the week.

As the week progressed, the high-speed stream influence waned and solar wind speeds decreased toward a slow solar wind regime, reaching roughly 370 to 450 km/s late in the week.

Geomagnetism

Geomagnetic activity was elevated at the beginning of the week, with unsettled to active levels and minor storm intervals occurring between 21:00 UTC on February 22 and 00:00 UTC on February 23 and between 03:00 UTC and 06:00 UTC on February 23 (NOAA Kp reaching 5- to 5; locally K BEL up to 5).

After this, geomagnetic conditions were mostly quiet to unsettled, with occasional active intervals both globally and locally.

International Sunspot Number by SILSO

The daily Estimated International Sunspot Number (EISN, red curve with shaded error) derived by a simplified method from real-time data from the worldwide SILSO network. It extends the official Sunspot Number from the full processing of the preceding month (green line), a few days more than one solar rotation. The horizontal blue line shows the current monthly average. The yellow dots give the number of stations that provided valid data. Valid data are used to calculate the EISN. The triangle gives the number of stations providing data. When a triangle and a yellow dot coincide, it means that all the data is used to calculate the EISN of that day.

PROBA2 Observations

Solar Activity

Solar flare activity fluctuated from low to moderate during the week.

In order to view the activity of this week in more detail, we suggest to go to the following website from which all the daily (normal and difference) movies can be accessed: https://proba2.oma.be/ssa

This page also lists the recorded flaring events.

A weekly overview movie (SWAP week 831) can be found here: https://proba2.sidc.be/swap/data/mpg/movies/weekly_movies/weekly_movie_2026_02_23.mp4.

Details about some of this week's events can be found further below.

If any of the linked movies are unavailable they can be found in the P2SC movie repository here: https://proba2.oma.be/swap/data/mpg/movies/.

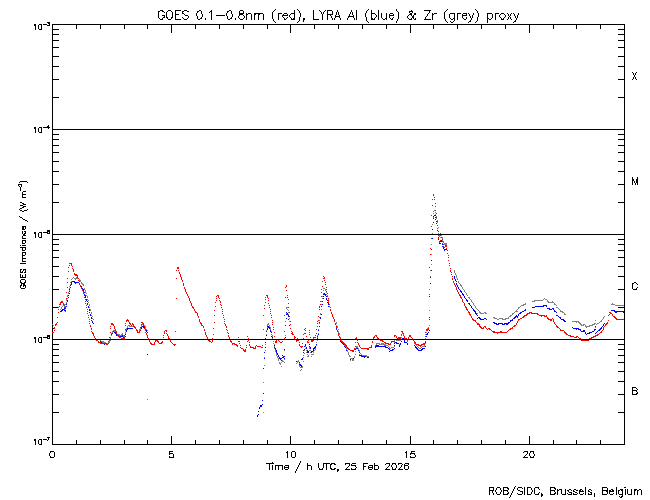

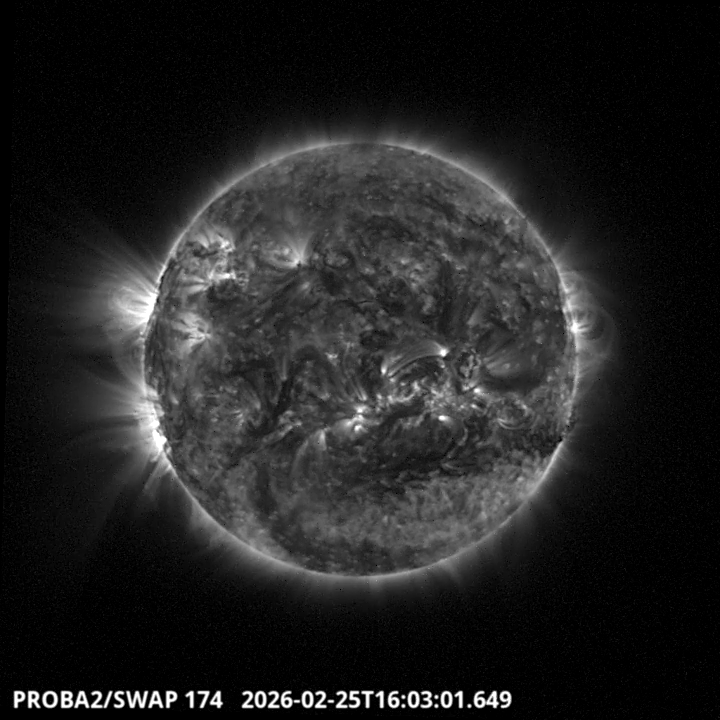

Wednesday February 25

The largest and only M-flare of this week was an M2.3, and it was observed by LYRA (top panel) and SWAP (bottom panel). The flare peaked on 2026-Feb-25 at 15:59 UT and occurred at the eastern limb of the Sun, originating from active region NOAA4380 (SIDC 803).

Find a SWAP movie of the event here: https://proba2.sidc.be/swap/movies/20260225_swap_movie.mp4.

Noticeable Solar Events

| DAY | BEGIN | MAX | END | LOC | XRAY | OP | 10CM | TYPE | Cat | NOAA |

| 25 | 1535 | 1559 | 1609 | M2.3 | 4380 |

| LOC: approximate heliographic location | TYPE: radio burst type |

| XRAY: X-ray flare class | Cat: Catania sunspot group number |

| OP: optical flare class | NOAA: NOAA active region number |

| 10CM: peak 10 cm radio flux |

Geomagnetic Observations in Belgium

Local K-type magnetic activity index for Belgium based on data from Dourbes (DOU) and Manhay (MAB). Comparing the data from both measurement stations allows to reliably remove outliers from the magnetic data. At the same time the operational service availability is improved: whenever data from one observatory is not available, the single-station index obtained from the other can be used as a fallback system.

Both the two-station index and the single station indices are available here: http://ionosphere.meteo.be/geomagnetism/K_BEL/

Review of Ionospheric Activity

VTEC time series at 3 locations in Europe from 23 Feb 2026 till 1 Mar 2026

The top figure shows the time evolution of the Vertical Total Electron Content (VTEC) (in red) during the last week at three locations:

a) in the northern part of Europe(N 61deg E 5deg)

b) above Brussels(N 50.5deg, E 4.5 deg)

c) in the southern part of Europe(N 36 deg, E 5deg)

This top figure also shows (in grey) the normal ionospheric behaviour expected based on the median VTEC from the 15 previous days.

The time series below shows the VTEC difference (in green) and relative difference (in blue) with respect to the median of the last 15 days in the North, Mid (above Brussels) and South of Europe. It thus illustrates the VTEC deviation from normal quiet behaviour.

The VTEC is expressed in TECu (with TECu=10^16 electrons per square meter) and is directly related to the signal propagation delay due to the ionosphere (in figure: delay on GPS L1 frequency).

The Sun's radiation ionizes the Earth's upper atmosphere, the ionosphere, located from about 60km to 1000km above the Earth's surface.The ionization process in the ionosphere produces ions and free electrons. These electrons perturb the propagation of the GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) signals by inducing a so-called ionospheric delay.

See http://stce.be/newsletter/GNSS_final.pdf for some more explanations; for more information, see https://gnss.be/SpaceWeather

The SIDC Space Weather Briefing

The forecaster on duty presented the SIDC briefing that gives an overview of space weather from February 23 to March 1.

The pdf of the presentation: https://www.stce.be/briefings/20260302_SWbriefing.pdf

Upcoming Activities

Courses, seminars, presentations and events with the Sun-Space-Earth system and Space Weather as the main theme. We provide occasions to get submerged in our world through educational, informative and instructive activities.

* Mar 16-18, 2026, STCE course: Role of the ionosphere and space weather in military communications, Brussels, Belgium - fully booked

* Apr 20-21, 2026, STCE cursus: inleiding tot het ruimteweer, voor leden van volkssterrenwachten, Brussels, Belgium - register: https://events.spacepole.be/event/260/

* Mar 23, 2026, STCE lecture: From physics to forecasting, Space Weather course by ESA Academy, Redu, Belgium

* Mar 25, 2026, The Belgian Space Weather centre, Space Weather course by ESA Academy, Brussels, Belgium

* Jun 15-17, 2026, STCE Space Weather Introductory Course, Brussels, Belgium - register: https://events.spacepole.be/event/256/

* Oct 12-14, 2026, STCE Space Weather Introductory Course, Brussels, Belgium - register: https://events.spacepole.be/event/257/

* Nov 23-25, 2026, STCE course: Role of the ionosphere and space weather in military communications, Brussels, Belgium - register: https://events.spacepole.be/event/259/

* Dec 7-9, 2026, STCE Space Weather Introductory Course for Aviation, Brussels, Belgium - register: https://events.spacepole.be/event/262/

To register for a course and check the seminar details, navigate to the STCE Space Weather Education Center: https://www.stce.be/SWEC

If you want your event in the STCE newsletter, contact us: stce_coordination at stce.be

Website: https://www.stce.be/SWEC