The Apollo 11 mission took place in 1969, during the maximum of solar cycle 20 (SC20). That maximum was stronger than the one of the current, nearly finished, solar cycle 24 (SC24). Thus, it might be worthwhile to take a look at the space weather conditions during the 16-24 July flight to and back from the Moon, and evaluate the associated risks to which the astronauts were exposed. Solar activity, geomagnetic activity, and particle radiation environment will be considered. To put things a bit in perspective, a comparison will be made with one of the more active periods during SC24, i.e. from 4 till 12 September 2017 (bottom lines of each table).

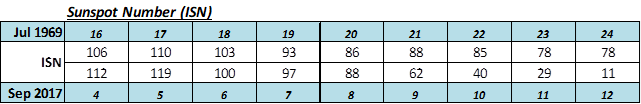

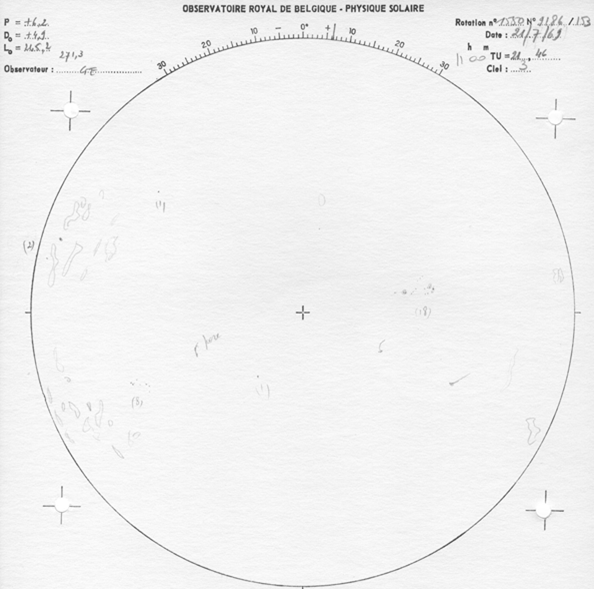

To evaluate solar activity, the obvious start is to take a look at the international sunspot number (ISN, as determined by SILSO). SC20 reached a smoothed maximum of 156.6 in November 1968, and the monthly sunspot number in July 1969 was still at 137.1. However, during the 8 days of the Apollo 11 mission, the daily sunspot number was at the low end, declining from values near 110 to around 80. See the table above, as well as the solar drawing below from the solar telescope at SIDC / USET on 21 July 1969, showing only 5 relatively small sunspot groups possessing simple magnetic configurations. These sunspot numbers are fairly similar to the ones from the comparison period in September 2017. In contrast, both at the beginning and the end of July 1969, the ISN reached significantly higher values around 200.

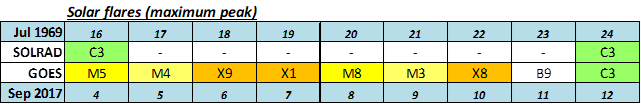

From the numbers, one would expect relatively low solar flare activity. Though there were no GOES spacecraft yet to observe the Sun in x-ray in 1969 -they started in 1976 only-, there were already the SOLRAD satellites (SOLar RADiation - data from NOAA / NGDC) observing the Sun in the same wavelengths (0.1-0.8 nm) as the GOES spacecraft. At the time, only flares larger than C3 were reported. The table below shows for each day the peak strength of the strongest flare. Clearly, and luckily, the Apollo 11 crew flew during a period of very low to low solar activity. In contrast, the period in September 2017 showed high solar activity with multiple strong flares (an X-class flare is 10 times stronger than an M-class flare, which in turn is 10 times stronger than a C-class flare). This was of course due to the magnetically very complex active region NOAA 2673 (see this STCE Newsitem for an overview of the activity).

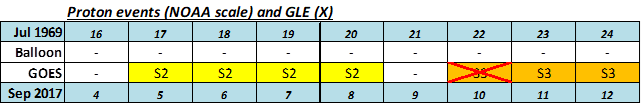

The radiation environment is more difficult to characterize, as -again- no GOES observations were present at that time to keep track of the proton flux. See this STCE Newsitem for info on intensity and historical strong proton events. Nonetheless, one can get an idea of the proton events from balloon measurements (e.g. Bazilevskaya et al. (2010) ; Table 1 is also available at NOAA / NGDC ). More importantly, there's the list of Ground level Enhancements (GLE - see this STCE Newsitem) maintained by the University of Oulu, Finland. Putting the data together (table underneath), it appears there were no strong proton events during the Apollo 11 mission and certainly no GLEs.

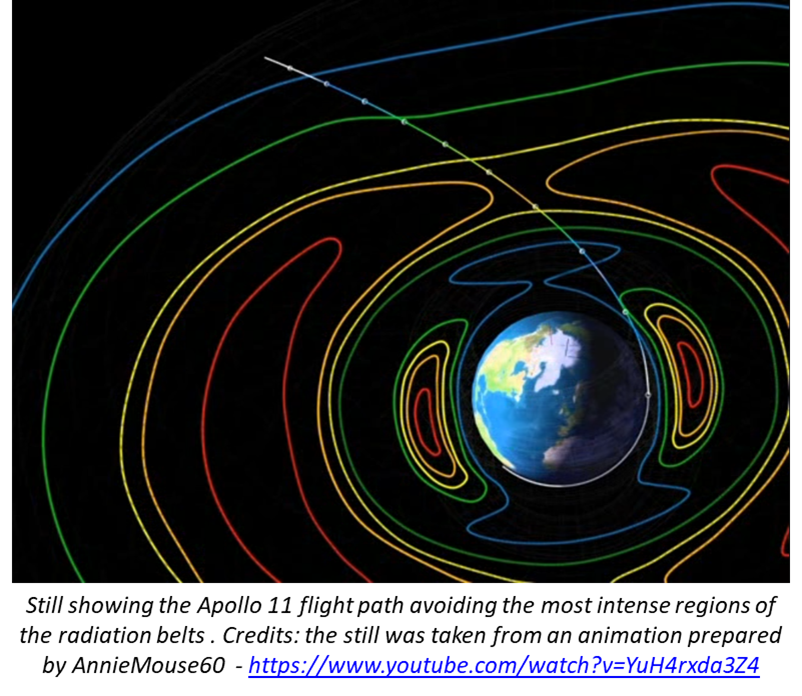

This meant safe conditions for the astronauts, who had to deal already with the Van Allen radiation belts (the trajectory was such that it avoided the most intense parts of these belts - see sketch underneath) and the galactic cosmic rays (GCR), but fortunately, the SC maximum implies lower levels of the harmful GCRs than during SC minimum. A subsequent NASA investigation indicated that "... Radiation doses to Apollo crewmen have been significantly lower than the yearly average of 5 rem set by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission for workers who use radioactive materials in factories and institutions across the United States. More significantly, Apollo astronaut doses have been negligible in terms of any medical or biological effects that could impair the function of man in the space environment. ..." (English et al., 1973). In September 2017, there were a moderate and a strong proton event (see here for the NOAA scales), but in particular the GLE of 10 September might have been cause for some concern, though the intensity of this event is way below the ones of e.g. 24 October 1989 or 14 July 2000, and is simply tiny compared to the monster GLE of 23 February 1956.

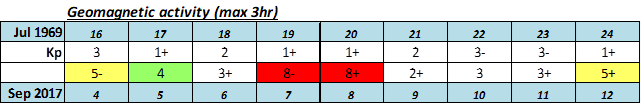

In view of the foregoing assessment indicating the low levels of solar activity, one could expect that also geomagnetic activity was low in July 1969. "Geomagnetic" pertains of course to the earth environment, but it is assumed here to be a good proxy for the space environment for the nearby Moon. The values of the Kp-index were taken, as available at the Kyoto World Data Center for Geomagnetism. With only quiet to unsettled geomagnetic conditions during the period, there were no threats from this site of space weather activity to the Apollo 11 mission. Of note is the moderately strong geomagnetic storm that took place on 26-27 July, just 2 days after the end of the Apollo mission. The table underneath shows that geomagnetic conditions were quite a bit more enhanced in September 2017, but also here no extremely severe geomagnetic storm (Kp = 9) was recorded.

One can conclude that space weather conditions were really favorable to the Apollo 11 mission. There were only a few small sunspot groups present on the solar disk, resulting in little or no flaring and as a consequence no particular extra threats from particle radiation or geomagnetic storms.