ESA’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft has discovered a multitude of tiny jets of material escaping from the Sun’s outer atmosphere. Each jet lasts for between 20 and 100 seconds, and expels plasma at around 100 km/s. These jets could be the long-sought-after source of the ‘solar wind’.

The solar wind consists of charged particles, known as plasma, that continuously escape the Sun. When the solar wind collides with Earth’s magnetic field, it produces the aurorae. Understanding how and where the solar wind is generated near the Sun has proven elusive and has been a key focus of study for decades. Now, observations by the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) onboard Solar Orbiter have taken us an important step closer.

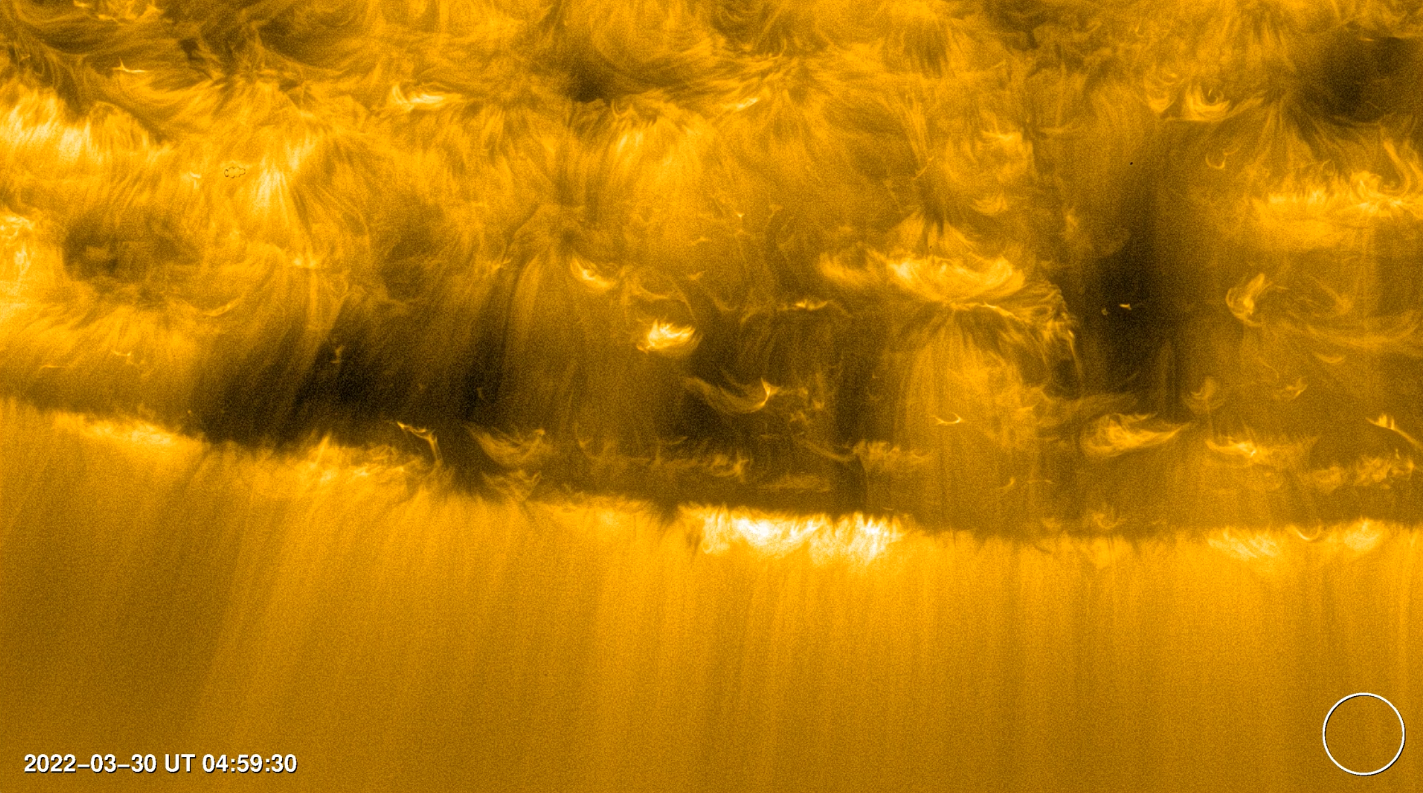

EUI is a telescope observing the Sun in extreme ultraviolet light. It is operated by the Royal Observatory of Belgium, and its unprecedented high-resolution and high-cadence images of the Sun’s south pole on 30 March 2022 reveal a population of faint, short-lived features that are associated with small jets of million-degree plasma being ejected from the Sun’s atmosphere. The results are reported in a paper just published in the Science journal.

Researchers have known for decades that a significant fraction of the solar wind is associated with magnetic structures called coronal holes – regions where the Sun’s magnetic field does not turn back down into the Sun. Instead, the magnetic field stretches deep into the Solar System. Plasma can flow along these ‘open‘ magnetic field lines. But the question was: how did the plasma get launched? The traditional assumption was that because the corona is hot, it will naturally expand and a portion of it will escape along the field lines, creating the solar wind.

“One of our results is that to a large extent, this flow is not actually steady and uniform, as was traditionally assumed. Rather, the ubiquity of the jets suggests that the solar wind from coronal holes might originate as a highly intermittent outflow,” says Andrei Zhukov, Royal Observatory of Belgium, a collaborator on the work who led the Solar Orbiter observing campaign.

The ubiquity of the tiny jets implied by the new observations suggests that they are expelling a substantial fraction of the material we see in the solar wind. And there could be even smaller, more frequent events providing yet more. “I think it's a significant step to find something on the solar disk that certainly is contributing to the solar wind,” says David Berghmans, Royal Observatory of Belgium, and principal investigator for the EUI instrument.

In the next years, we expect EUI to register these tiny jets in a better perspective than now, as Solar Orbiter will gradually incline its orbit towards the polar regions. All involved will be eager to see what fresh insights they can collect because this work extends further than our own Solar System. The Sun is the only star whose atmosphere we can observe in such detail, but it is likely that the same process operates on other stars too. That turns these observations into the discovery of a fundamental astrophysical process.

“Picoflare jets power the solar wind emerging from a coronal hole on the Sun” by L. P. Chitta et al. is published in Science, vol. 381, issue 6660, pages 867-872, doi: 10.1126/science.ade5801.

More details in the ESA story.

Solar Orbiter is a space mission of international collaboration between ESA and NASA, operated by ESA. The EUI instrument was built by an international consortium led by the Centre Spatial de Liège and is operated since the launch (2020) by the Royal Observatory of Belgium, with funding and support from the Solar-Terrestrial Centre of Excellence (STCE) and the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office (BELSPO).

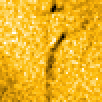

This mosaic of images shows a multitude of tiny jets of material escaping from the Sun’s outer atmosphere. The images come from the EUI telescope onboard ESA’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft. They show up as dark streaks across the solar surface in this mosaic. The images are ‘negatives’ meaning that although the jets are displayed as dark, there are really bright flashes against the solar surface. Each jet lasts for between 20 and 100 seconds, and expels charged particles, known as plasma, at around 100 km/s. These events could be the long-sought-after source of the ‘solar wind’, the constant outflow of charged particles that comes from the Sun and flows through the Solar System.

This movie (click on the image) was taken by the EUI telescope onboard ESA’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft. It shows a ‘coronal hole’ near the Sun’s south pole observed on 30 March 2022. Subsequent analysis has revealed many tiny jets taking place during the observation. They show up as little streaks of bright light across the image. Each one expels a quantity of charged particles, known as plasma, into space. These events could be the source of the solar wind, the constant outflow of charged particles that comes from the Sun and flows through the Solar System. Magnetic structures known as coronal holes are a source region of the solar wind. These are regions where the Sun’s magnetic field does not turn back down into the Sun. Instead, it stretches into the Solar System. It could be that the tiny jets discovered in these images launch the plasma that feeds the solar wind, as they travel away from the Sun.

The circle indicates the size of the Earth for scale.